Why Aren't We Stopping the Landlords?

The solution to the current housing crisis is not to simply "build more houses and the low rents will come." We need to tackle high rent at the source. But, first: talk to the people suffering from it

Publisher’s Riff

There are four major questions that remain, largely, still unanswered by the so-called “urbanist” or “YIMBY” community of experts, advocates, policymakers and organizers who claim that the way to fix a housing affordability or cost-of-living crisis is to, simply, build more housing stock …

How do you, truly, stop landlords or property managers from constantly setting and raising exorbitant rents?

Where is the study or research proving that the building of more housing stock significantly decreases rent or stops rent increases?

Where is the study or research proving that the building of more housing in a city stops the displacement of income-distressed or “low-income” residents and eliminates housing insecurity and homelessness altogether?

When doing the research and making these decisions to build, who exactly are you talking to?

We want to first acknowledge that housing is an extremely complex issue (I’d argue primarily because housing is not the human right it should be). There are so many different layers of onion to peel. But, that peeling is necessary to help people understand the scope of struggle they’re facing.

Hence, the first question is a very important one because, clearly, we find ourselves in a volatile situation where rents are very high and unsustainable: Who exactly can afford rent that’s increasing and moving far beyond an individual or a household’s ability to afford it? As Axios reports …

Asking rents in the second quarter were 23% higher nationwide compared to the same period in 2019. These are the rents landlords charge to new tenants, as opposed to renewal rents — the price you pay when you renegotiate your lease. Those going up, as well, but not as much.

How do rent increases of this magnitude work our for the nearly 40 percent of the population that looks like this? From Pew …

… and particularly when, as Pew notes, 61 percent of the people who rent are in the lowest income quartile and nearly 90 percent of people are with net worths below the 25th percentile rent? How exactly does increasing rent help their situation in any way?

When having this conversation about rising rents, national discourse assumes that rents - like inflation - come from out of nowhere … or “it just is what it is.” There’s no consideration of the fact that both present a form of price-gouging precipitated by human operators exerting command over certain industries and market sectors. We should understand that we wouldn’t have high rents if not for the people who set rents: landlords. And, that keeps leading back to the original question above in varying forms: If we know this is 1) unsustainable activity that 2) leads to more “inflation” and that 3) leads to more people unable to afford things like rent which then 4) ultimately leads to social instability and unrest when you have more people without stable housing why, exactly, would we keep on allowing landlords to add to that destabilizing situation with unnecessarily exorbitant rents?

Where exactly is the policy solution that puts a stop to that?

When posing that question, urbanist visionaries always answer with this: oh, easy, just build more housing. This is a crisis of scarce supply (they say) so if you build more supply to meet increased demand, prices won’t increase. But, is that it? One often cited 2019 study from the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in conjunction with the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia contends that …

New buildings decrease nearby rents by 5 to 7 percent relative to locations slightly farther away or developed later, and they increase in-migration from low-income areas. Results are driven by a large supply effect—we show that new buildings absorb many high-income households—that overwhelms any offsetting endogenous amenity effect. The latter may be small because most new buildings go into already-changing areas. Contrary to common concerns, new buildings slow local rent increases rather than initiate or accelerate them.

But do they really? There are lots more questions arising from what’s masquerading as an ultimate solution. Mainly: it doesn’t comport with displacement realities on the ground where - as much as incoming and primarily White populations want to deny - eviction, forced-to-sell and forced migration trends continue at a rapid pace, coupled with the stressors of crime, broken schools and bad employment prospects in many spaces. The other question: Are they actually calculating low-income residents or are they calculating spaces or neighborhoods that are designated or viewed as “low-income”? Is this more than just data based off Zillow? Is it data based off the real-life experiences of low-income families who are barely making it? Because, remember, there are a lot of those families out there.

Running the Numbers

And if the rent is already high in a certain area or city, how does a 5-7 percent decrease really help? Who is that 5-7 percent decrease designed for? Take Philadelphia for example where, according to Apartment List, the average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment is $1,143 and the average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment is $1,332 …

Even with decreases of 5-7 percent on the 1-bedroom rent, you’d experience savings ranging from $60-$80, thereby decreasing rent to anywhere between $1,083 down to $1,063 per month. For that average 2-bedroom apartment, you’d experience savings ranging from $70 - $95, or somewhere between $1,262 down to $1,237.

One urbanist evangelical pushing “build more” as the end-all-be-all solution also posits that average 2-bedroom rent in Philly is actually more than Apartment List …

Here, he and others are telling on themselves: Who exactly are we talking about in Philly who can afford $1,750 a month rent, especially when Area Median Income (AMI) in Philadelphia is $49,000? In this case, that level of rent - a combined $21,000 for 12 months - is actually 43 percent of annual AMI income, well over the standard housing cost “30 percent rule,” which many experts have long derided as being unrealistic and too rigid. An even if we apply a decrease of $90 - $125 as “Will” here dryly submits, that brings rent down to anywhere from $1625 down to $1,660 per month: that’s still 40 percent - 41 percent of an AMI resident’s full income, still well over the standard and still burdensome “30 percent rule.” So, once again: who exactly are we talking about that this would seem like “a lot of money to me”? Left unchallenged this becomes a very White-splaining, White-dominated and “for middle-class Whites only” conversation. We understand everyone, including middle-class professional Whites moving into cities or wanting urban amenities, have needs, too - but, those needs should not, cannot continue to come at the expense of other communities, primarily Black, Brown and low-income, that are constantly beset with a barrage of structural challenges in the struggle space.

Let’s also take into account what individuals, living 0-50 percent of AMI, have to contend with in terms of living costs in Philadelphia. According to the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator, this is “the income [one person] needs in order to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living” in Philadelphia …

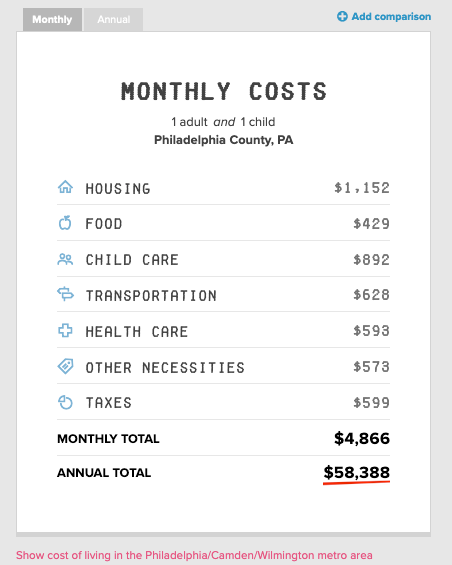

The costs suddenly spike (watch housing) when you add one child to the mix …

Here are two adults with one child …

But, what’s it like when you’re alone raising two?

So, with these accumulated necessities how does saving “$90-$125” seem like a lot of money? How does this allow an individual or family, especially when places like Philadelphia are grappling with low AMI and a near 30 percent poverty rate, to afford rent at anywhere from $1,200 - $1,800 per month … and, even if they can, still be able to afford everything else?

If decreases in rents were truly that good and that substantial, why are so many Black, low-income and other distressed residents in places like Philadelphia and elsewhere still complaining about high rent and being forcibly removed from their space because of rent they can’t afford? Are we talking to them about these struggles? Is that experience referenced or considered in this research?

This isn’t an honest public conversation, really, about rent or housing costs, is it? Because …

It completely leaves out a needed policy prescription to insensitive and predatory landlords, including “Mom & Pops” or individual owners who can’t afford to be in the landlord business in the first place and are passing the cost of their own financial burdens along to mostly unsuspecting and innocent families

It’s not pausing to have direct conversations with those hit the hardest by unsustainable high rents and low-income conditions. Pro-build research makes little effort, if any, to talk directly with low-income residents and just assumes those residents will adjust to price fluctuations that are favorable to people in their income bracket: middle-class White people. Urbanist “YIMBY” and build-it-all advocacy avoids (like the plague) having conversations with and engaging in the needed coalition building with original residents in distressed communities and simply asking “What do you need?” and “What do you think is the best solution?” and then working from there.

Bottom line: On principle, no one’s stopping anyone from building all they want (although, in this climate crisis ravaged apocalypse we’re living in, do we really need to build or do we need to repurpose?). You can build all the new housing you want. That, however, is still not stopping the property owner from feeling compelled to constantly raise the rent or the owners in other sectors of the economy from raising prices on other goods and products. That’s an occurrence we can all agree on and, aside from adding another building or two so “market forces” can solve it, we need to come up with something a whole lot better than that.