What Happened to Addressing Inequality?

It’s clear that economic disparities are rising in cities, not falling. A "YIMBY" obsession with more housing construction can lead to greater inequality, not less

Pete Saunders | a Corner Side Yard feature

My father, a retired AME Church pastor, would on occasion start preaching with a story about a pastor preaching a particularly fantastic sermon. The pastor was heaped with praise by his congregants after service. The following Sunday he preached the exact same sermon, to the puzzlement of the church members. The Sunday after that he did the same thing, and church deacons decided to talk to the pastor after service.

“Pastor,” they said, “today makes three consecutive Sundays you’ve preached the exact same sermon. How long do you intend to keep doing this?” The pastor replied: “I’ll move on when the church members start living the lessons of the message.”

I’m about to apply the same approach to American metro inequality discourse.

It wasn’t that long ago – in 2008, with the election of President Barack Obama – that the issue of economic inequality in America was presumed as solved. The nation had elected its first Black president and it was viewed as evidence that perhaps we were ready to enter a “post-racial” era. It was a demonstration of our commitment to the ideal that “all (wo)men are created equal.”

But it didn’t last long.

The Gaps Getting Wider

The fallout from the financial crisis and Great Recession over the ensuing years revealed the unequal nature of economic recovery. Gaps widened between the nation’s haves and have-nots: knowledge economy coastal cities versus the rural hinterlands; sunny locations promoting affordability and lifestyle versus gritty manufacturing-based cities. And it wasn’t only inter-regional inequality that was exposed. Intra-regional inequality, or the way we view differences in the quality of life of people within the same region, became more apparent. It refreshed concerns about who was thriving in the new American economy, and who wasn’t. The resentment among white working-class voters that pushed Donald Trump into the White House in 2016 added another layer to inequality discourse.

More recently, concerns of inequality hit another fervent peak in 2020, when the tragic deaths of George Floyd, Ahmad Arbery and Breonna Taylor were protested by people worldwide. Inequality discourse probably reached a peak in the summer of 2020. Since then it’s faded considerably as the nation turned its attention to other important matters like surviving the COVID pandemic, the January 6th insurrection, mass shooting tragedies, the war in Ukraine, the reversal of Roe v. Wade, obscenely high gas prices and existential threats to our system of government.

Racial, economic and social inequality, particularly in our nation’s cities, hasn’t disappeared. At a minimum, inequality levels remain the same, and perhaps widened. If anything, our nation has become much better at identifying inequalities and their impact on American society, but no better at all at resolving them.

The COVID pandemic was a case study in how America identifies inequality, yet fails to address it. Early in the pandemic we recognized that people of color were hospitalized and dying from COVID at substantially higher rates than whites, even when controlled for economic factors. We knew that the divide between the professional class that had the ability to weather the pandemic working from home, and the service class that was urged to work in direct contact with the public to keep the economy moving, was largely a divide between whites and people of color.

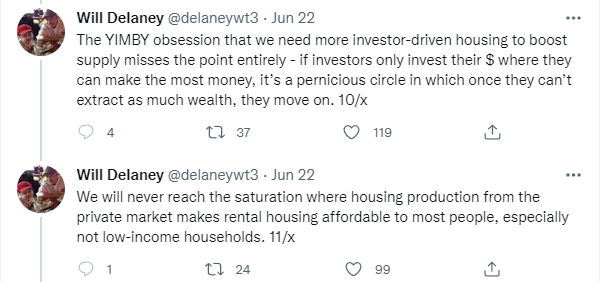

I was reminded of all of this once again during some Twitter debates earlier this month. A tweet thread about a proposed rent control measure in St. Paul, MN was receiving push-back from developers and YIMBYs because it was seen as a constraint on development. Twitter user Will Delaney made a particularly salient point:

I followed up with some admittedly acidic comments of my own:

I wanted to express concern that the policies preferred by YIMBYs, a growing and rather influential group of urbanists dedicated to expanding housing construction in metro areas to make it more affordable, could lead to greater inequality, and not less. I said that I saw this as being particularly true in cities and metro areas that had slower economic and population growth, as both wealth and poverty become more concentrated.

Then the blowback commenced.

I won’t revisit the details of the blowback, but I do want to make clear my position on the revitalization of our cities and metro areas.

A Revitalization Paradigm

I became an urbanist because I recognized the potential of cities and wanted to improve them. I’ve said many times, here and in other spaces, that growing up in 1970’s Detroit has shaped my perspective of cities. At a time of widespread suburban growth where residents were willingly discarding cities, I wanted to fuel their comeback.

The last 30 years of urban revitalization in American cities has been the best opportunity in a century to bring greater prosperity to cities and to create greater parity between city neighborhoods and suburban municipalities. Even as an urbanist, I did not foresee the rise of cities that began in the 1990’s. However I was more than ecstatic to see it happen and to become a new foundation for revitalization. A new focus on what I call the “experiential advantage” of cities was making them more attractive to a greater number of people.

However …

It’s clear that economic disparities are rising in our cities, not falling. Three recent reports speak to this. The Economic Innovation Group’s Distressed Communities Index found that at the ZIP code level nationwide, more people are living in prosperous communities than ever before. Yet, it was mostly accomplished by affluent people moving into already affluent communities. The Brookings Institution’s Metro Monitor 2021 came to the same conclusion, and spoke even more directly to a growing concentration of affluent residents with a corresponding dispersion of people in disadvantaged neighborhoods in metro areas. In other words, densifying affluent communities existing near hollowing disadvantaged communities. Why? Because segregation policies and practices in our major cities continue to have an impact on the opportunities, fortunes and lives of our city’s residents.

Housing affordability does not automatically lead to greater economic and social equity. I don’t disagree for one bit that increasing the supply of housing in high-cost markets will bring prices to affordable levels. Yet, I’ve always maintained that increasing supply is a benefit that accrues to the people and place where the new housing is built. It does nothing to address the stigma of place that we, consciously or unconsciously, assign to neighborhoods. That has a tangible impact on their ability to come back.

What could be an effective strategy for one metro area type could be problematic for another one. What works for a super-charged economy in coastal metros might not be the best response for metros in the middle of the country that have had a more tempered pattern of growth, even stagnant or in decline.

There are a lot of people who fail to recognize the relevance of this analogy, but I’ll try again. The post-World War II era was indeed the era of a housing crisis in the U.S. Most people are familiar with the national response to the lack of housing at the time – the expansion of development that would define today’s notion of suburbia. The post-WWII expansion, however, coincided with the plateau (and later decline) of many cities throughout the country. The surplus of housing that was built in the suburbs accelerated the decline of many of those cities.

I want to avoid a similar outcome.