Not Everyone is Equal During Heatwaves

With heat more frequent & intense, historically disenfranchised populations are the most vulnerable

a B|E Green feature

presented by Reality Check on WURD, airs Monday - Thursday, 4-7pm ET, streamed live at WURDradio.com, in Philly on 96.1 FM / 900 AM | #RealityCheck @ellisonreport

New York City utility ConEdison’s recent decision to cut off electricity in majority Black Brooklyn neighborhoods could be a very troubling and sobering sign of times to come. As climate change transitions into climate crisis, and heat waves becomes much longer and more intense, the danger to historically vulnerable Black and urban populations will be very real.

Publication Grist provides a rather frightening account of what happened in New York City this past Sunday:

Almost half Americans spent the weekend trying to beat record-breaking temperatures. But for a large swath of New Yorkers, staying home and turning on the air conditioning was not an option, as utility company Con Edison cut cooling power for several hours in several of the heat-strangled city’s most diverse and low-income neighborhoods.

The outages, which started Sunday night, affected nearly 50,000 ConEdison customers, many of whom were among the city’s most at-risk for heat-related death. Extreme heat takes more than 600 lives each year, making it deadlier than any other type of weather-related disaster.

ConEdison asked customers in southeast Brooklyn to bear with the heat as it decreased voltage by 8 percent in the area to protect its equipment and make repairs after some circuits failed. The utility requested that residents shut off their ACs “if not needed for health or medical reasons.”

“I have one question for Con Ed: Why’d they choose us?” said Flatlands resident Stanley Henriquez in an interview with local news outlet Brooklyn Daily Eagle on Monday. “Why are we the ones that have to suffer for the bigger power grid? We pay like everybody else.”

One problem here is that utility shut-offs targeting low-income and primarily Black communities is nothing new. The NAACP focused in on this as an environmental justice issue in 2017 with a briefing worth reading here. Utility companies, whether servicing electricity, heat or water consumers, routinely complain of utility overuse, particularly in densely populated cities. But, when looking to alleviate the stress on utility grids, low-income or economically strapped residents get hit with either predatory billing or planned cut-offs and outages, such as what happened in New York City recently.

It is a good question: Why choose those neighborhoods? Of course, ConEdison isn’t putting that burden on NYC’s wealthy Manhattan district, which more than likely uses much more power.

The other problem is how heat waves are being perceived, despite the abundance of climate crisis warnings, events and impact. Cities, in particular, are still viewing heat waves as a nuisance, with some populations or demographic groups more susceptible to heat-related illness or death than others. But, it is not being viewed - as of yet - as a major public health emergency; instead, it’s something requiring, simply, “cooling center” and public pool or water fountain response. New media coverage, typically, acknowledges heat waves and heat wave alerts from local governments - but, media refuse to comprehensively unpack how some populations are suffering under heat waves much more than others; there is no exploration of how heat waves are much more than a nuisance for low-income communities, but actually a battle for survival. Many of these households have no air conditioning and face reduced access to relief such as shade from tree canopy. Cooling centers facilitated by municipalities also have their limitations.

Michelle Klug notes in AJ+ …

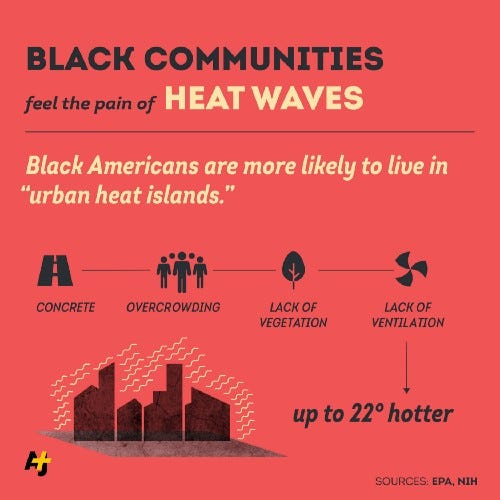

Across the country, black Americans are more likely to live in warmer neighborhoods than white Americans, and are 2.5 times more likely to die of heat-related causes such as heat stroke. Climate change has brought not only a steady increase in average temperatures (16 out of the past 17 warmest years have occurred since 2001), but also longer, stronger heat waves, which are intensified in certain urban areas.

Crowded, mostly concrete urban areas with little tree cover heat up fast. Heat radiates off of roads and buildings with little ventilation in a pattern called the heat island effect. In some cases these neighborhoods, which also tend to be occupied by low-income residents and minorities, can be 22°F hotter than surrounding areas.

The most recent set of heat waves in the United States were most intense in the South, Northeast and some Midwest portions of the country …

These are regions where we also find the highest concentrations of Black populations …

Forecasters and meteorologists could serve as key leaders helping mobilize communities around this issue. Sadly, they aren’t. Most rarely admit or report, even as heat waves are occurring, that these are very serious and alarming events. Instead, they are minimized and trivialized with aphorisms, jokes and “stay cool” quips. That has the effect of not only dismissing the impact heat waves are having on vulnerable populations, but it removes an important element of public pressure on governments. Forecasters, however, are afraid of being viewed as political (depending, largely, on the ownership and ideological leaning of that outlet), even as heat waves - and the health consequences - are based on clear, irrefutable science. Meanwhile, heat waves - without any global plan to mitigate them - will grow longer in days …

With heat waves more frequent and increasingly dangerous, the onus of emergency awareness and preparedness shouldn’t just fall on governments and media. Disproportionately impacted communities themselves must pressure their own institutions, advocates and internal infrastructure to respond adequately with emergency planning. Black churches, for example, should be a front-line organization on this topic, serving not only as cooling facilities, but also as funding networks providing air cooling units for households without such. Civil rights organizations should do more than just monitor the situation, as well, from partnering with local and state government agencies (the federal government remains questionable) to coordinating with policymakers and medical institutions.