It's Not Smart To Ignore America's Illiteracy Problem

Munoz | CLMI

Illiteracy is on the rise in the U.S. - and it’s not just a problem for America’s youth, it’s also a challenge for just as many adults. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (the NAEP known as “America’s Report Card”) shows dramatic drops in reading and math scores to their lowest levels since the early 2000s when dramatic improvements were on the rise. Now, according to the NAEP, 40% of 4th graders are “below basic” reading; more than 33% of 8th graders read at the same level. Between 1990 to now, the average ACT college admissions score was 19.4 - on a scoring scale of 1 to 36. For a variety of reasons, 2013 was the pivot point, as a University of Virginia study observes …

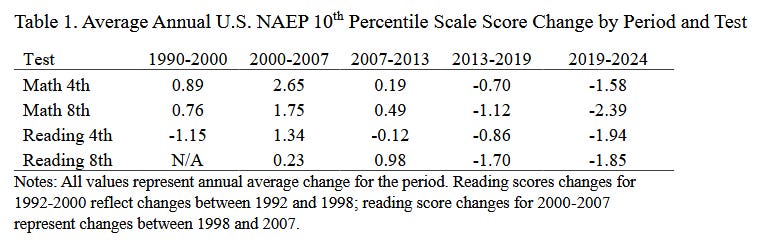

2013 has been employed as the year in which learning losses began. The signs of learning loss began before actual reductions were experienced, however. The early 2000s were marked, on average, by large achievement gains: between 2000 and 2007, 8th grade math scores at the 10th percentile increased by 12 scale score points (0.30 SD). Thereafter, score-increases declined. Between 2007 and 2013, scores increased by only 3 scale score points (0.07 SD) — before falling 6 points between 2013 and 2019 (0.17 SD). Similar trends also occurred in 4th grade reading and math, and in 8th grade reading (Table 1). The forces behind the large increases of the early 2000s had thus begun to dissipate by about 2007, turning to decreases about 2013.

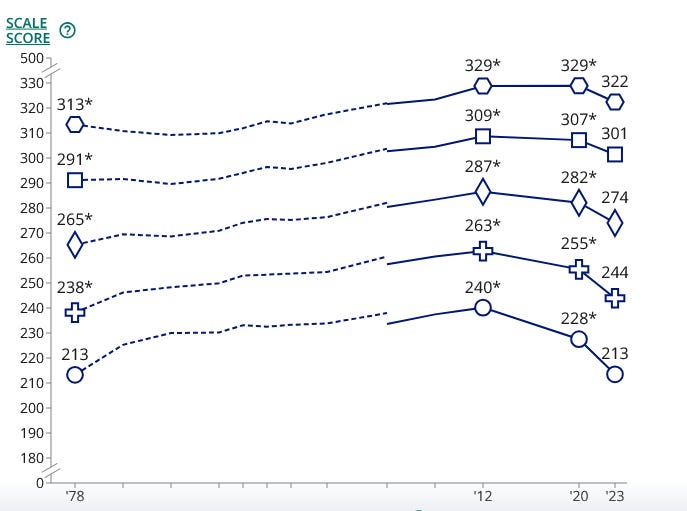

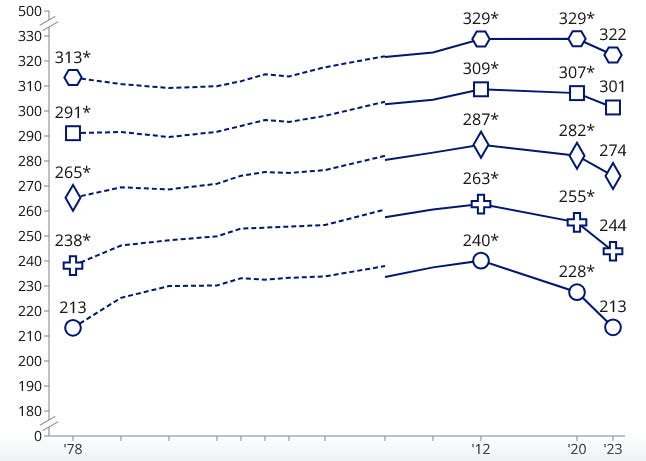

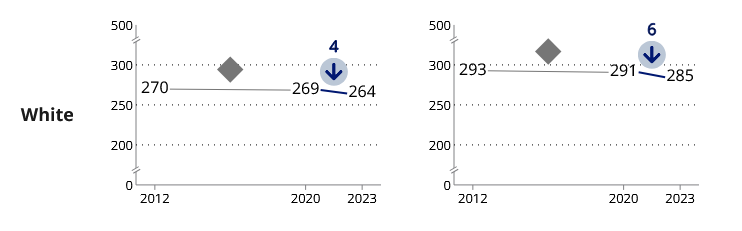

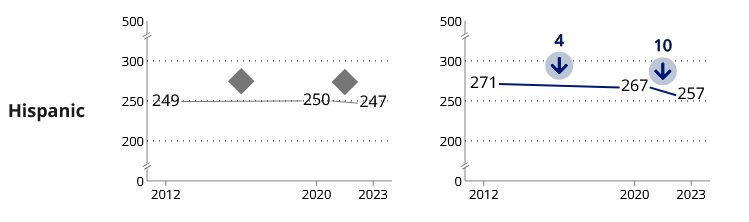

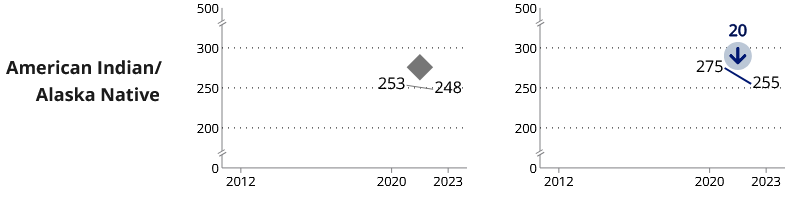

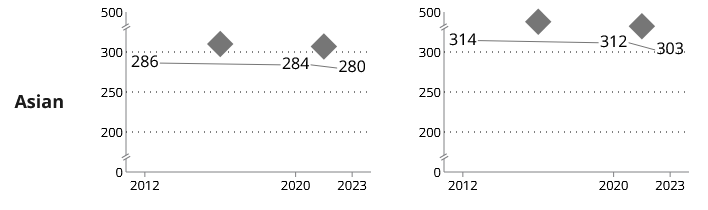

We see progressive dips in reading and math scores worsening since 2012, according to the NAEP, as notes in the University of Virginia study …

Reading

Math

Research, including the NAEP, points to inequality as a culprit - or, at least, a growing gap between different demographics that no one can ignore. Declines among white students since 2012 were 6 points in reading and 8 points in math, respectively …

Declines over that same period have been much more pronounced for other, much more socio-economically challenged racial demographics, including Black, Latino and Indigenous students.

Black reading scores dipped 10 points since 2012, in addition to a 20 point drop for math scores since then …

Readings scores for Hispanic students are still low compared to those of white students, yet remain relatively flat. Yet, there was a 14 point drop in math since 2012 …

Indigenous students have seen 5 point dips in reading since 2020, and a troubling 20 point dip during that very short time period.

Asian student scores are the highest among all demographic groups …

A number of issues could explain this. Policymakers, experts, educators and advocators often point to underfunded schools as the root of the problem. For example, an underfunded school may not be able to afford the attention each student deserves, meaning that a large portion of students who need more attention or suffer from a learning disability will get left behind compared to their peers. Children in Massachusetts enjoy the highest literacy rates, while New Mexico struggles with the lowest - Massachusetts spends, on average $17,058 per student a year, New Mexico only spends while $9,987. This example of a massive funding gap might explain or offer some insight into how funding affects students: What may seem like only a few thousand dollars actually makes a huge difference in terms of how far students progress. Students who aren’t set up with the proper resources to learn, will not only be affected academically, but they will also suffer socially and economically.

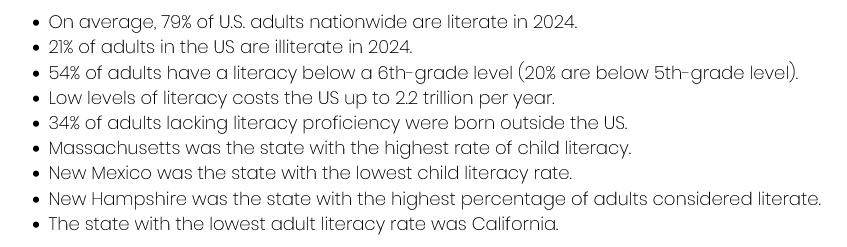

From poverty to unequal access to resources, to high incarceration rates among academically underperforming student groups. If these problems persist, we see a common thread: illiteracy. As that trend worsens among young people, it will grow into the adult population. Meanwhile, the National Literacy Institute ranks the United States 36th in reading and math literacy …

In states, New Hampshire has the highest adult literacy rate, while California has the lowest. One major difference in these states is that English has a higher immigration rate. That about tracks: About 34% of adults considered illiterate were born outside the U.S., with lack of literacy in immigrants linked to lack of committed funding for programs like ESL (English As A Second Language).

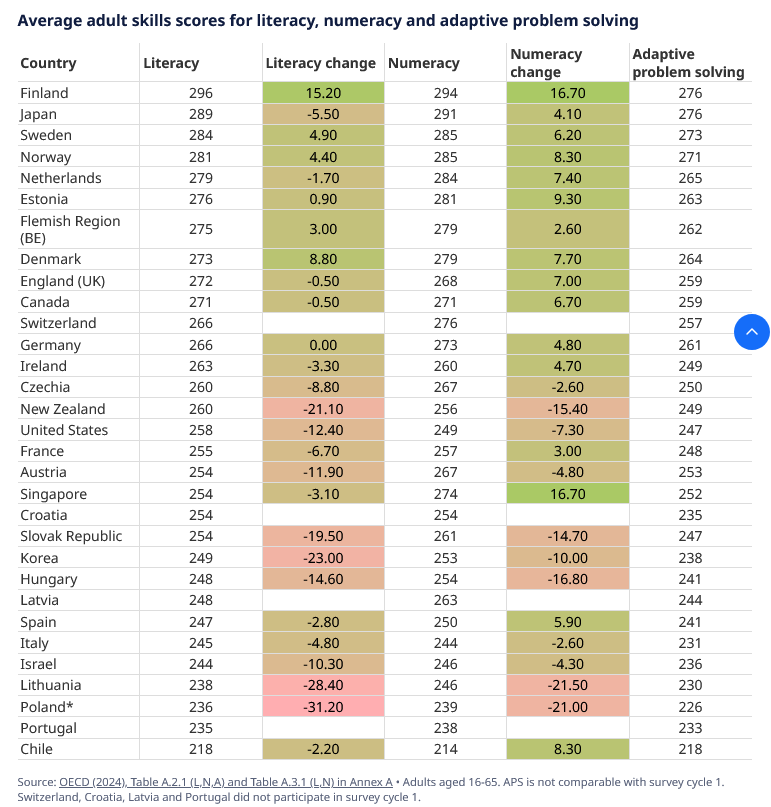

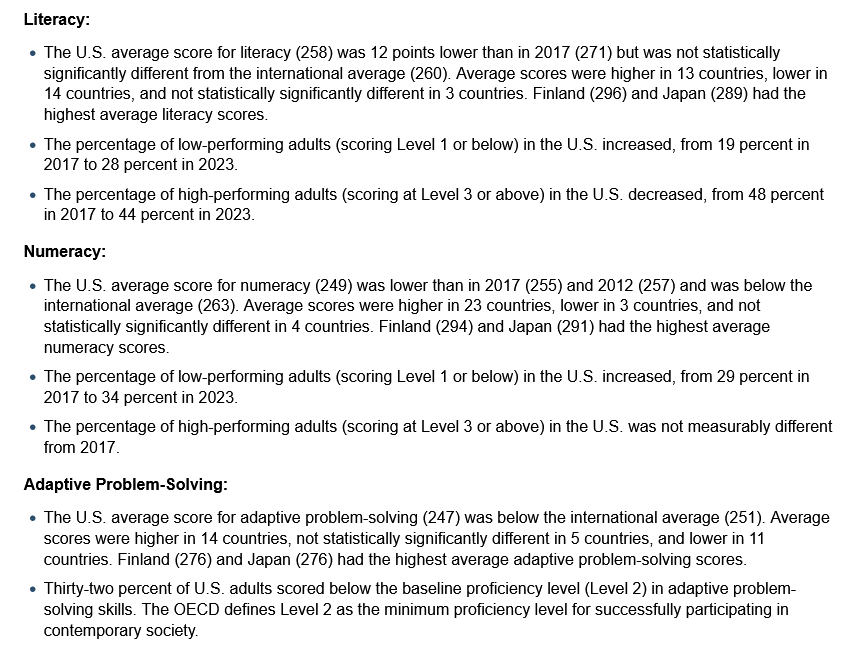

American adult reading and math literacy are in the bottom half of 31 countries scored by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In addition, U.S. adults continue to lag behind the OECD average for reading, math and adaptive problem-solving skills …

Still, the National Center for Education Statistics shows a somewhat different picture, recently arguing that …

The literacy skills of working-age U.S. adults were on par with the international average in the latest round of a major international study of basic cognitive and workplace skills.

Yet …

There is a ‘dwindling middle’ in the U.S. in terms of skills,” NCES Commissioner Peggy G. Carr explained. “Over time, we’re seeing more Americans clustered at the bottom levels of proficiency. The result has been a widening skills gap between adults at the higher and lower skill levels compounded by a growing number of very low-skilled adults. In fact, the U.S. gap in numeracy between the highest and lowest skilled adults is the widest among all countries

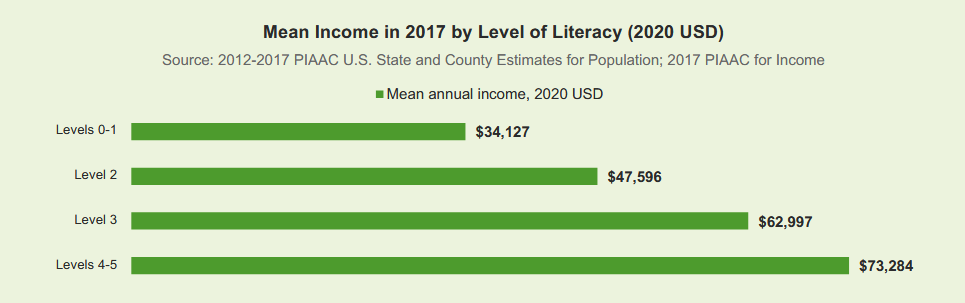

As illiteracy increases, poverty rates increase along with it. If someone lacks literacy, including reading and math proficiency, they are (naturally) on a path to earn less, as a Gallup study found …

The average annual income of adults who reach the minimum level for proficiency in literacy (Level 3) is nearly $63,000, significantly higher than the average of almost $48,000 earned by adults who score just below proficiency (Level 2) and much higher than those at low Levels of literacy (Levels 0 and 1), who earn just over $34,000 on average.

The cycle is repetitive and destructive, as low-income areas are typically the most illiterate. For example, Mississippi, one of the nation’s poorest states with one of the lowest household incomes, is also one of those states with the highest literacy declines. In a study, the National Center for Education Statistics surveyed 12,330 adults in the U.S. and found that Mississippi had the highest illiteracy rate.

With literacy linked to high poverty, the problem only continues to grow. A larger segment of the population less literate not only translates into higher poverty rates, but as the Gallup study argues, it leads to a significant cost in economic productivity: illiteracy accounts for a $2 trillion loss in national economic output or 10% of GDP. That damage to GDP starts in childhood, defined by low funded school districts and lack of innovation from educators, along with improper use of funding set aside for academic improvement and an unwillingness to push for a better standard, as Idress Khaloon in The Atlantic argues …

[T]here’s another explanation, albeit one that progressives in particular seem reluctant to countenance: a pervasive refusal to hold children to high standards. A seemingly plausible culprit, and a familiar boogeyman for progressives, is insufficient spending. The problem with this tidy explanation is that it’s not tethered to reality. School spending did not decline from 2012 to 2022. In fact, it increased significantly, even after adjusting for inflation, from $14,000 a student to more than $16,000. In short, schools have demanded less and less from students—who have responded, predictably, by giving less and less. During the pandemic, Congress appropriated a gargantuan sum of money, $190 billion, to ameliorate learning loss, most of it as part of the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan. (For scale, this is roughly the sum recently given to the Trump administration to fund its border wall and immigration-enforcement agenda.) States were given latitude to spend their funds as they saw fit, which, it seems, was a mistake. Instead of funding high-quality tutoring programs or other programs that benefited students, districts spent money for professional development or on capital expenditures such as replacing HVAC systems and obtaining electric buses.

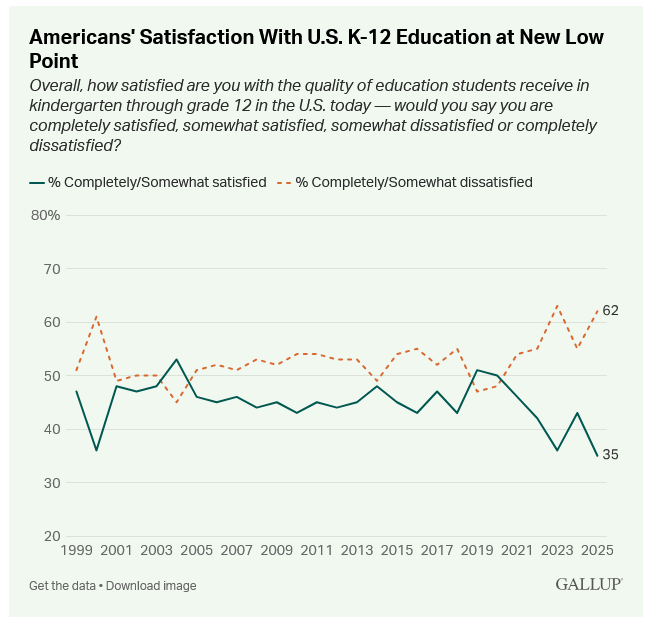

Literacy is critical from the beginning of childhood moving forward, and the nation’s future hinges on it. Clearly, the broader public agrees. A 2025 Gallup poll found 62% of Americans dissatisfied with K-12 education …

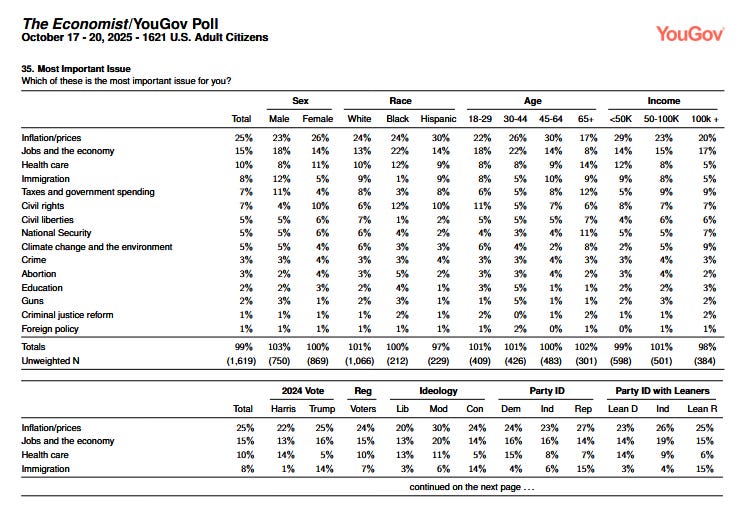

Yet, despite the future economic and global hazards illiteracy present, the broader public routinely ranks education at the bottom of most important issues …

As the illiteracy crisis grows, the public may be underestimating the scope of the problem at its own peril. This is one reason why it’s important to properly fund and resource classrooms. Policymakers, along with educators and school district leaders, must put every effort into providing students with the right level of attention. That will turn them into literate adults who will, ultimately, improve their communities.

VICTORIA MUNOZ is a Fellow at the Civic Literacy and Media Influence Institute at Learn4Life