It's Not a "Labor Shortage" - It's a Wage Shortage

It's crucial to debunk the anecdote-laden myth of a "massive labor shortage" that's resulting in the premature cutting of essential pandemic-relief benefits

Publisher’s Riff

A wave of 21 states thus far have decided to shut down extended federal unemployment benefits, the extra $300-a-week that have helped carry many of their residents through a pandemic economy that’s not fully recovered. The reason: “generous unemployment benefits” (which is a constant and very misleading media refrain based on acceptable societal stinginess) are keeping people at home and thus driving a critical “labor shortage.”

With so many states axing federal unemployment benefits - which were set to expire in September - there has been little counter-narrative to push back against an assumption based on anxious anecdotes versus what data show. That will lead to more states either outright rejecting federal benefits or claiming (as in the case of Pennsylvania) that specific types of extended relief are no longer needed due to signs of fewer unemployed people. Yet, there is no real “labor shortage” happening: workers are rejecting wage and benefit shortages in a market filled with too many low-wage jobs. Many workers have calculated that they’re in an even more precarious state if forced to take a low-wage and high health risk job (with few or non-existent benefits) that can’t keep up with current costs of living. Hence, is it worth the risk? Economic Policy Institute’s Heidi Sheirholz lays out a beautiful rebuttal of the dominant “labor shortage” theme ..

One question people raise is whether the expanded pandemic unemployment benefits keep workers from taking jobs. Right now, for example, unemployed workers who receive unemployment insurance benefits get not just the (very meager) level of benefits they would get under normal benefits formulas, but an additional $300 a week. That means that some very low-wage workers—like many restaurant workers—may receive more in unemployment benefits than they would at a job. Is this making jobs hard to fill? There was a lot of fuss about this same question a year ago, when workers were getting a $600 additional benefit a week. There were several rigorous papers that looked at this question, and they all found extremely limited labor supply effects of that additional weekly benefit. If the $600 a week wasn’t keeping people from taking jobs then, it’s hard to imagine that a benefit half that large is having that effect now.

Sheirholz also makes another important point that should raise concern and also further obliterates the “labor shortage” argument …

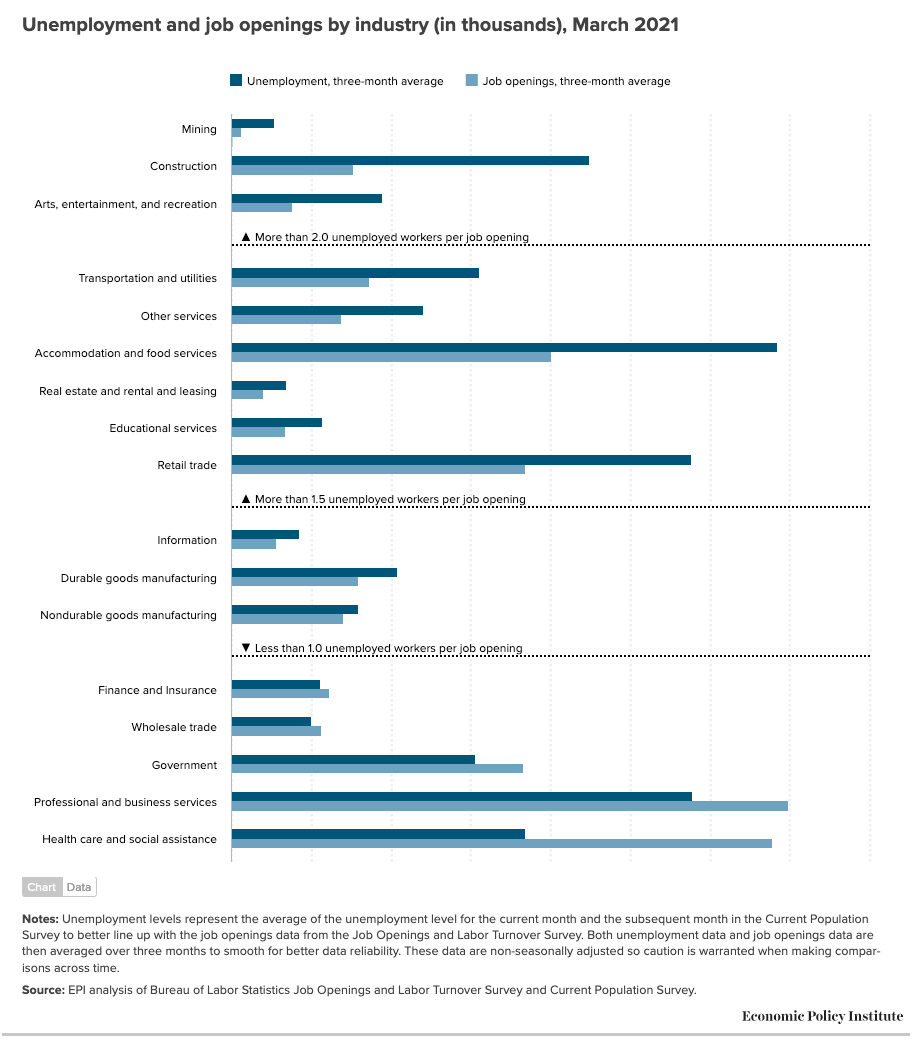

[T]here are far more unemployed people than available jobs in the current labor market. In the latest data on job openings, there were nearly 40% more unemployed workers than job openings overall, and more than 80% more unemployed workers than job openings in the leisure and hospitality sector.

Wage Growth

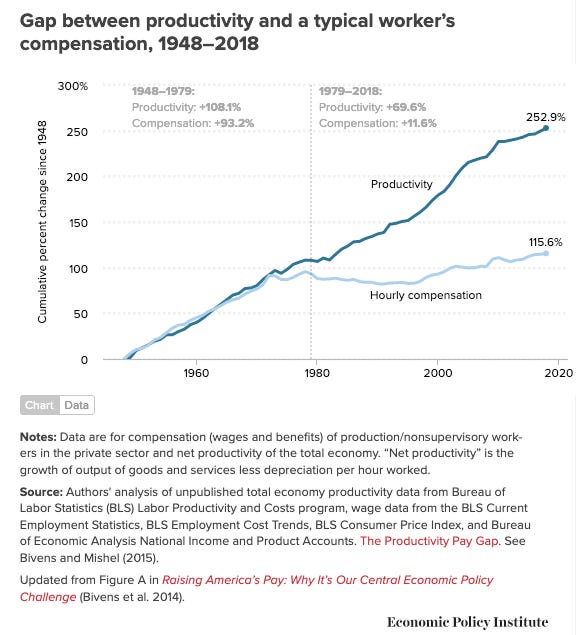

Wage shortages were always a big problem long before pandemic. First: with the federal minimum wage standard still set at $7.25/hour, there’s not much policy push on employers to raise wages in industries already suffering from sub-standard wages. Second: the current conversation on “labor shortages” could present a major opportunity for public discourse to understand how truly obscene current wage shortages are, particulary at a time of increased living costs and other pressures. But, more importantly, we should be having a discussion on how much U.S. productivity has spiked over the past several decades while wages have, generally, remained flat. When that gap is illustrated, it’s just striking and quite sobering to look at …

This is why clear cut data is absolutely important in conversations like this versus a tendency to embrace anecdotes. There are certain interests at work who seem eager to have workers earn as little as possible while having their purses/pockets simultaneously squeezed by increasingly harder living. Many workers seemed to have, instinctively, caught on to that and almost triggered a movement moment. That moment will now be short-lived. Removing a crucial survival layer of additional unemployment benefits is not an experiment in whether or not those same benefits are a drag on the labor market. It is, instead, a cruel form of forced take-it-or-go-hungry labor not too far removed from its cousin, slavery.