"Energy Justice": What It Is and Why Everyone Should Start Thinking About It

a Smart Surfaces Coalition feature

In recent years, the just transition movement has increasingly focused on energy, in what some have referred to as “a new front-line in environmental justice research and activism” (Sze and London 2008). The concept of energy justice focuses separately on energy concerns among the broader issues addressed in the environmental justice movement (Bickerstaff et al. 2013; Jenkins et al. 2018) by integrating social equity principles into energy systems. An overlap of environmental justice and energy justice is the siting of energy infrastructure: an energy justice approach considers whether the location of energy infrastructure makes energy more affordable or accessible for historically disadvantaged households, whereas an environmental justice approach broadly considers whether the location of energy infrastructure unequally burdens a nearby community. Key to the energy justice movement is access to new energy system benefits and access to clean and affordable energy for everyone. With energy justice, energy systems can support economic growth in addition to energy security for individuals and communities.

An energy transition can provide enormous opportunities for cleaner energy sources, new employment, and technological innovation (Cha 2020; Miller 2022, 2023). However, it also can exacerbate existing disparities afflicting communities of color and low-income neighborhoods or reduce access to opportunities that accompany energy transitions (Carley and Konisky 2020). Despite the shared manifestations of racial–ethnic and income-based disparities, research has shown that racial–ethnic factors have a larger effect on disparities than income-based factors. For example, a review of national exposure to air pollution from 1990 to 2010 found absolute exposure disparities were larger for racial and ethnic groups than for income categories. There is an absence of racial–ethnic indicators in the federal government’s definition of disadvantaged communities, so we’re focused on income-based disparities of the U.S. energy system. However, it is important to acknowledge and understand the distinction between racial–ethnic and income-based factors to develop appropriate solutions.

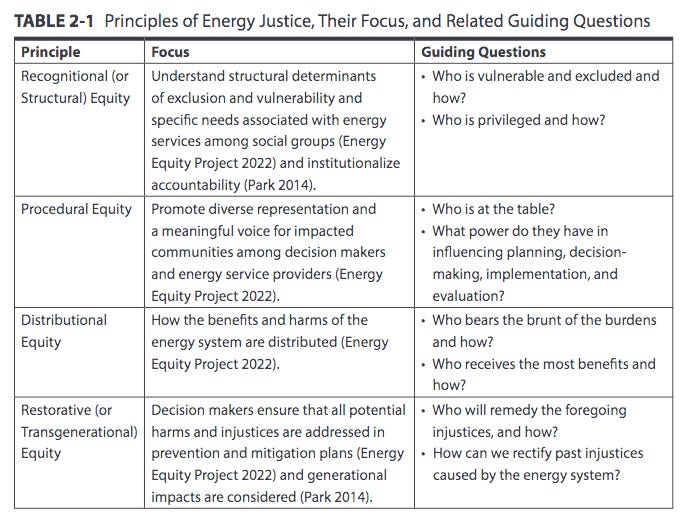

We define a “just energy transition” as the process of transforming the energy system by ensuring that all communities, workers, and social groups are included in the processes toward and outcomes of the net-zero future through the incorporation of the principles of energy justice. Incorporating energy justice principles in the energy transition will provide the nation an opportunity to prioritize human-centered approaches in energy system design and policymaking so that the costs and benefits of energy services are distributed fairly (Tarekegne et al. 2021), thus making it just. Table 2-1 below illustrates four principles of energy justice, their focus, and guiding questions …

The energy justice principles provide an analytical and decision-making framework for researchers, advocates, policy makers, and communities to understand the human and social dimensions of energy systems and their inequities (Sovacool and Dworkin 2014). This chapter largely focuses on recognitional, procedural, and distributional equity in its discussion of barriers, examples, and recommended solutions. However, restorative equity provides important context-setting for recognitional, procedural, and distributional equity and is therefore the foundation of all equity frameworks (Spurlock et al. 2022). The integration of energy justice principles needs to be both a bottom-up approach beginning with community-led programs sharing lessons learned and best practices and a top-down process beginning with federal adoption and implementation of these principles.

The term “intersectionality” describes how structures and systems of oppression — such as racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and redlining — heighten the effects of discrimination, exclusion, and social inequality on communities marginalized by multiple systems (Cooper 2016; Crenshaw 1989; Dhamoon 2011; Goldsmith et al. 2022; Roman 2017). An intersectional approach to energy justice emphasizes how multiple systems of marginalization and human identities interact to increase exposure to environmental harms and reduce access to energy and environmental benefits (Crenshaw 2017; Goldsmith et al. 2022; Kaijser and Kronsell 2014). Efforts have analyzed how intersectionality affects distributional inequalities to create energy inequities and have made recommendations to target the social and political practices of exclusion through which these inequalities are generated (Schlosberg and Collins 2014; Walker 2009). Relatedly, “[e]nergy democracy” recognizes such intersectional factors as it focuses attention on strengthening inclusive decision-making processes and democratic institutions, often through decentralized energy projects (Berthod et al. 2022; Nadesan et al. 2023).

The current energy system has led to disparities in energy affordability, the ability to afford one’s energy bills, with disadvantaged communities experiencing most of the negative costs. Intersecting systemic inequities result in households’ experiencing unequal access to basic energy, unequal ability to meet basic energy needs, and unequal availability of the income needed to obtain energy. Energy burden, energy insecurity, and energy poverty are increasingly severe instances of social inequities that in turn relate to unequal vulnerability to other stressors. Analyzing energy system impacts across intersecting socioeconomic and demographic metrics allows for the identification of individuals who are most vulnerable, underserved, or marginalized (Hernández et al. 2014; Jenkins 2018). Energy poverty, the lack of affordable, reliable, and environmentally sound energy services (Reddy 2000), will be directly addressed through the incorporation of energy justice into the U.S. energy transition.

Energy insecurity is the inability to adequately meet basic household energy needs over time (Hernández et al. 2016). It is attributed to several factors, including inefficient housing and appliances leading to more inefficient energy use; lack of financial resources to afford air conditioning and heat pumps; and unequal access to cooling or heating that may lead some residents to dangerously under-heat or under-cool their homes (Hernández et al. 2014). These energy inequities amplify other existing health, educational, and socioeconomic disparities and further reinforce obstacles to civic participation in society (Bouzarovski 2018). For example, households with children are more likely to engage in dangerous financial and behavioral coping strategies, to be disconnected from energy services, and to be energy insecure (Carley et al. 2022; Konisky et al. 2022; Memmott et al. 2021). Furthermore, children in moderately and severely energy insecure households are more likely to experience food insecurity, hospitalizations, and developmental concerns than children in energy secure homes (Cook et al. 2008; Hernández et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2007).

Energy burden, the percentage of gross household energy costs spent on energy, is a metric that operationalizes energy affordability and identifies groups in need of targeting policies and investments to reduce high energy burdens (Cong et al. 2022). According to a survey by Indiana University’s Energy Justice Lab, nearly 40 percent of Latino households and more than 26 percent of Black households said that they were unable to pay their electricity bill (Carley et al. 2022) and thus experience high energy burden. Additionally, compared to White respondents, Latino and Black respondents were 80 percent and 30 percent, respectively, more likely to have their service disconnected by their utility provider, which often comes with additional fees to restore electricity services (Carley et al. 2022). Poor housing conditions, including lack of insulation and old rooftops, and a lack of transportation options, such as accessible public transit and safe biking, tend to perpetuate high energy burdens (Drehobl and Ross 2016).

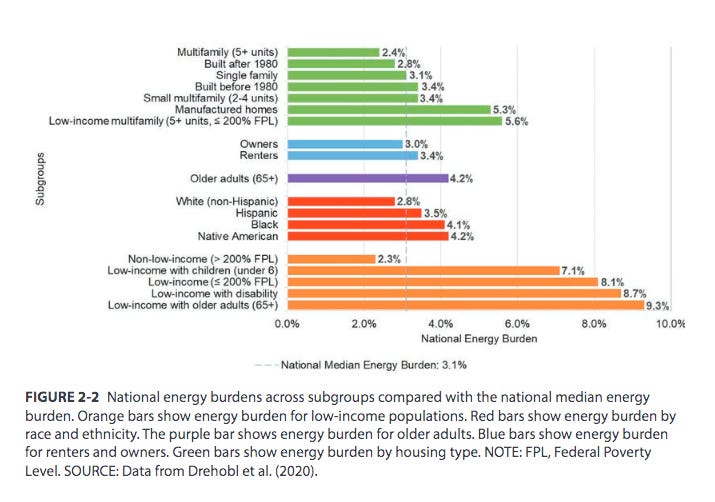

Households within disadvantaged communities in the United States often spend a larger fraction of their household income on utilities for heating, cooling, and other home energy services than the general population (Drehobl and Ross 2016; Drehobl et al. 2020). Data from the Department of Energy (DOE) Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) Tool,5 designed to improve the understanding of states, communities, and stakeholders about energy characteristics, shows that the average energy burden for low-income households is 8.6 percent (DOE 2020), which is more than double the national median of 3.1 percent. Figure 2-2 illustrates the comparison of the national median energy burden with the median energy burden of certain groups …

However, average energy burden does not accurately reflect existing discrepancies in utility rates, especially between rural and coastal urban areas. During the development and implementation of programs addressing energy burden, regional differences must be considered and adjusted for.

Increases in the cost of energy often force families to decide whether to spend more of their household income on energy or on something else such as rent, education, food, and transportation (Brown et al. 2020). Disadvantaged communities tend to have older or less energy-efficient homes, which increases household energy expenses. These households often either cannot afford to upgrade to energy efficient products or are renters and do not have the ability to do so. Subsidies and programs such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) are designed to mitigate these burdens (Brown et al. 2020; Hernández and Bird 2010). However, these programs have historically been underfunded and tend to be intentionally short-term solutions that ensure that utilities—not the households—are protected against potential debts and disconnection of services. Programs designed to mitigate energy burden also suffer from significant implementation failures (Carley et al. 2022; Farley et al. 2021) and tend to be hard for consumers to navigate.

The benefits of the energy transition to date have not always been equally distributed. The energy burdens of inefficient appliances, homes, and vehicles persist in low-income populations and for households of color. Conversely, wealthier consumers can afford the relatively high up-front costs of energy-saving and emission-reducing technologies (e.g., high-efficiency air conditioners, smart meters, electric vehicles, heat pumps, and rooftop solar), which have lower operating costs and so decrease their total energy costs (Carley and Konisky 2020; Drehobl and Ross 2016; Ross et al. 2018). Such energy-saving devices are often cost prohibitive for and not prioritized by low-income households, especially when a working fossil fuel–based device (e.g., gas-powered furnace) is already in place (Agyeman et al. 2016; Lukanov and Krieger 2019; Morrissey et al. 2020). To address the challenge of energy affordability and associated burdens and achieve energy justice, it is important to recognize these existing burdens and the intersecting factors that influence them.

Disadvantaged communities are often economically excluded from, reluctant to adopt, or unaware of opportunities to install low-carbon technologies. This might be owing to fear of hidden costs, program limitations, lack of trust in government, inadequate outreach and information, insufficient capacity, and inequitable and predatory financing (Madrid 2017; Méndez et al. 2020; Vogelsong 2022). For example, split incentives between owner and tenant create barriers to the energy transition, as building owners do not have any incentive to pay for retrofits, energy efficiency, or safety improvements if only tenants receive the benefits from decreased energy bills (Besley 2010; Boudet 2019; Segreto et al. 2020). Solutions for the tensions caused by split incentives need to be designed to create tangible benefits for both parties.

From the report entitled “Accelerating Decarbonization in the United States: Technology, Policy, and Societal Dimensions: Consensus Study Report” released by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024.