College Tuition as the Ultimate Racial Barrier

A refusal to explore (and acknowledge) the racist origins of crushing higher education costs

#BlackEdChat

presented by Reality Check on WURD, airs Monday - Thursday, 4-7pm ET, streamed live at WURDradio.com, in Philly on 96.1 FM / 900 AM | #RealityCheck@ellisonreport

As the House Financial Services Committee earlier today labored and sighed heavily over what’s assessed as a $1.5 trillion student loan debt crisis, there’s always an invisible elephant in the room on the question of how it arrived at this point in the first place. Meaning: have we ever wondered if rising college tuition was itself a deliberate sinister plot to just, simply, keep certain groups of people out of the success space … while making them, literally, pay - out of pocket - for that exclusion?

In a recent interview by The Atlantic’s Joe Pinsker, profiled anthropologist Caitlin Zaloom gives this answer on how higher education costs rose so quickly:

College used to be a lot cheaper for families, because there was more funding from the government. If you think about the biggest educational systems, like the University of California system or the City University of New York system, these universities were free or practically free for decades. That was in part because of a belief that higher education was essential for the national project of upward mobility, and for having an educated citizenry.

So middle-class families didn’t always have to pay for college with debt. The shift began in the 1980s, in terms of a changing political philosophy. President Ronald Reagan’s budget director, David Stockman, said in 1981, “If people want to go to college bad enough, then there is opportunity and responsibility on their part to finance their way through the best way they can.” When those who argued that college is a private benefit framed it like that, it became logical to say that education should be paid for by the people that it benefits. And so in the 1990s, the vast expansion of loans for higher education began.

And, so, yes, it is very fascinating and peculiar how Zaloom casually - rather unwittingly - leaves race and racism out of this answer. True: “college [did] used to be a lot cheaper for families,” now how about that … but, during a conveniently Leave it to Beaver era when Jim Crow did not apply to a certain persuasion of people who were permitted go to college on a mass scale without barriers or prohibitions. Few know that, for example, the often lauded and famed “G.I. Bill,” which is credited with building the American middle-class with unemployment, housing and higher education benefits during the post-World War II boom, was in fact racist in its implementation and application: Black WW II veterans were actively denied those benefits. Nothing more basic than History.com to illustrate this:

Black veterans in search of the education they had been guaranteed fared no better. Many black men returning home from the war didn’t even try to take advantage of the bill’s educational benefits—they could not afford to spend time in school instead of working. But those who did were at a considerable disadvantage compared to their white counterparts. Public education provided poor preparation for black students, and many lacked much educational attainment at all due to poverty and social pressures.

As veteran applications flooded universities, black students often found themselves left out. Northern universities dragged their feet when it came to admitting black students, and Southern colleges barred black students entirely. And the VA itself encouraged black veterans to apply for vocational training instead of university admission and arbitrarily denied educational benefits to some students.

So, if you’re an anthropologist or education expert, you can’t leave this glaring detail out.

You also can’t leave out that the Reagan administration was channeling neo-Confederate resentment against Civil Rights Movement gains when engaging in wholesale cutbacks to national education priorities. Which brings us to a correlation between two trend lines that we rarely see examined, at least in a vivid way.

Camilo Maldonado on rising tuition costs over the years in Forbes:

The average for all four-year institutions comes out to $26,120 per year. This brings the total cost of attendance to an astronomical total of $104,480 over four years. The comparable cost for the same four-year degree in 1989 was $26,902 ($52,892 adjusted for inflation). This means that between the academic years ending in 1989 and 2016, the cost for a four year degree doubled, even after inflation. Over that period, the average annual growth rate for the cost to attend a four-year university was 2.6% per year. At face value, 2.6% growth doesn’t seem too awful.

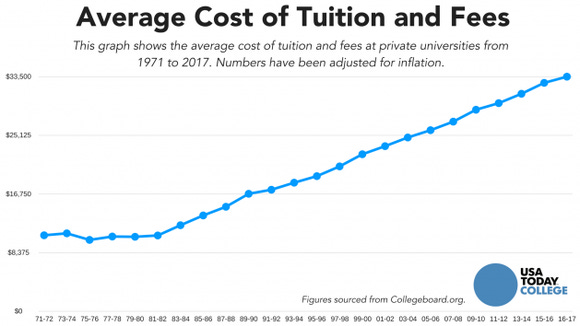

Here’s a graph of how bad that’s been:

That trend line conveniently matches the trend line of Black college enrollment and degree attainment rates illustrated below. Black degree attainment is still dramatically lower than White degree attainment, but it shows some steady rise since 1970 …

Racial gaps in degree attainment persist, but it’s still interesting to see how the struggle towards Black degree attainment is matched by a war against rising college tuition. Notice how that markedly flattens during much of the 1980s and into the 1990s, but shows increases by the very late 1990s and into early 2000s …

We see how, at the same time, tuition not only increased, it soared. Funny how it worked out like that.