Case Study: Philadelphia, Literally, Has the Worst Air About It

Green Living Plan: Not only is Philadelphia still the poorest big city in the United States, but it also holds some of the most unbreathable air, too. Policymakers there act like it's not a problem.

Charles D. Ellison | Publisher’s Note

It remains both astounding and bewildering how bad Philadelphia’s air quality is, and how much Philadelphia itself refuses to talk about it.

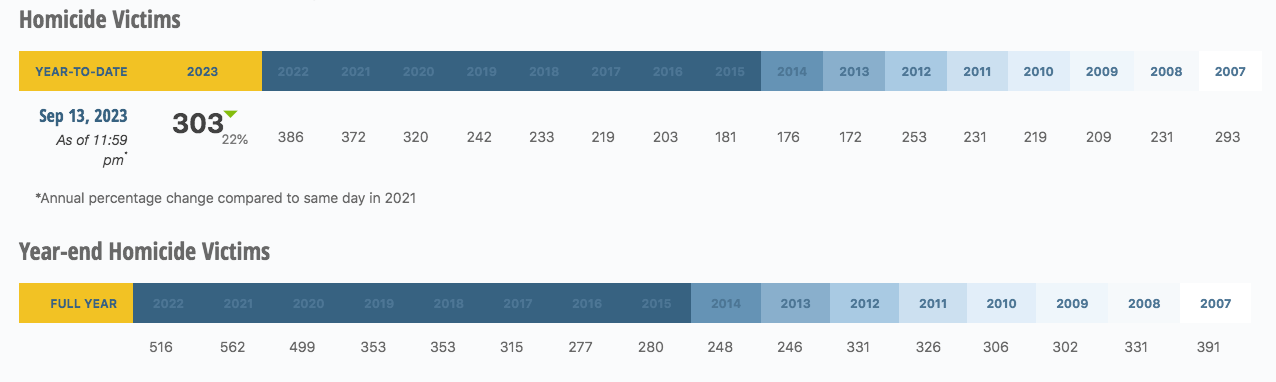

You can even make the argument that it’s the most important conversation it could have as blistering heat waves continued to close school classrooms early yet another year and the hottest days in human history presented a fresh fistful of vicious health complications. Because, since when could you even have a conversation or breathe without air, correct? How do human beings live without oxygen, right? Even as homicides show slight signs of waning – down 22 percent currently compared to last year – the nearly 300 murders so far (and we haven’t even hit mid-September) are still far above where they were before pandemic. They’re also still markedly higher than New York City’s 240 murders so far this year – and that’s a city nearly 8 times the size of Philly, 9 million people versus 1.6 million.

Clearly, something is in the air (as they say) in Philly that Philadelphians themselves don’t want to talk about. So bad is that air that as climate crisis-triggered wildfire smoke from Canada enveloped our region in June, Philadelphia quickly rose to the choking top as having “the worst air quality compared to all major cities.”

While the wildfire threat has subsided (for now) air quality in Philly continues lingering as a deeply worrisome issue: at this writing, climate crisis temperatures (because, let’s be clear, this level of September heat wave is abnormal) reached 95 degrees – and that’s not including the additional heat index from humidity, pollution and random junkyard fire (a Philly thing).

While, the American Lung Association’s 2023 State of the Air report removed Philly from its “worst 25 list” because of some improvements, Philly’s Air “moderate” Quality Index (or AQI) of 64 at the time of this writing on one of the hottest days in the region on record is troubling compared to other cities much larger than where you’d expect the reverse. New York City has a population of nearly 9 million – yet, its AQI is just one point above Philly’s. Los Angeles is nearly 4 million, yet, its AQI is below Philly’s at 55. Chicago has a population of 3 million, and yet it maintains a refreshing 19 on the AQI. Houston’s population of 2.3 million, in a state notorious for its anti-environment record, has an AQI of 66. Cities much larger in size, density and population are faring much better in air quality than Philadelphia perhaps because they’re paying much more attention to the issue and they’re not grappling with as much poverty for a big city. Or, maybe, their political leadership just happens to prioritize it in a way that Philly’s won’t.

But what is noticeable is that Philadelphia is a trap of synchronized air pollution variables. “We have a confluence of multiple refineries in our region, a major airport, a major ports shipping complex, as well as the I-95 corridor. So, we have a great complexity of very large air pollution sources, clustered in one part of our city,” as Jane Clougherty noted in a 2021 WHYY interview. “And that really has not been appropriately disentangled. Because in part, we’ve been thinking about pollutants that are nationally relevant, not really thinking about the things that are relevant here in Philly. And that’s really a shift we need to make.”

It’s a desperate shift considering Philly’s also had nine major junkyard fires to date this year that add to the problem, with no visible sense of urgency from government officials and inspectors. What becomes doubly alarming is that few have grasped that nearly a quarter (21 percent) of all Philadelphia children are struggling with asthma – that's more than double the national average of 9 percent. So, why would you add junkyard fires to that? Penn’s Regional Center for Children’s Environmental Health adds more to say that, actually, it’s three times the national average.

The bulk of that impact falls on, as always, Black and Brown children living in the lowest income neighborhoods or nearest the largest pollution centers, whether that’s the airport, a boulevard or highway or sources of gas such as the methane leaking all throughout city neighborhoods.

Policymakers (who, we presume, breathe the same air) should be deeply concerned, but they’ve not shown any signs to date that they are. The two mayoral nominees, who’ve avoided public campaigning altogether this past summer, have removed anything referencing the environment from their lexicon – even as the city’s air quality fast deteriorates and a pollution-triggered climate crisis burdens top others.

The Violence and Bad Air Connection

We get it, public safety is the number one priority for public conversation right now. But wouldn’t you know that a number of studies have shown direct correlations between bad air quality and high violent crime rates: as Colorado State University stressed in 2019 …"a 10 microgram-per-cubic-meter increase in daily exposure to particulates was found to correlate to a 1.4 percent increase in violent crimes. The team also found that a 0.01 parts-per-million increase in exposure to ozone was associated with a 1.15 percent increase in assaults. The researchers calculated that a 10 percent reduction in particulate levels could save $1.4 billion in crime costs per year, a "previously overlooked cost associated with pollution.”

Others such as the London School of Economics discovered the same association, with crimes increasing by nearly 3 percent each time the AQI spiked above 35 (Philly’s AQI is nearly double that, remember?). A 2021 NIH-published study looking at air pollution linkages between indoor and outdoor crimes concluded that

[S]pecifically, greater efforts need to be made in the prevention of comprehensive domestic violence by considering environmental factors. Therefore, local government officials should consider the relation between air pollution and their domestic violence prevention strategies.

The research literature on what to do continues to grow as climate-crisis grows worse.

City and state officials, from the outgoing mayor to the new one, and especially City Council, could find their moment here. City Hall and Harrisburg should be teamed up to devise thoughtful and rapid response strategies other than the obligatory announcement of a new initiative or goal set to some distant year when it’s too late. They’re not, much less on other city-wide environmental catastrophes or an ambitious vision for how the city adjusts to climate crisis impacts. When Philly found its citywide tap water system virtually undrinkable for a week, the Chair of the Council’s Environment Committee Katherine Gilmore Richardson was sending out press releases about Spring clean-up, Women’s History Month celebrations and the Free Library’s ‘One Book, One Philadelphia’ program. And while no one should diminish the cultural importance of the above, it can’t be ignored how odd it is that the Chair of the city legislature committee tasked with overseeing city environmental crises wasn’t issuing official statements on the water crisis and hasn’t, to date, been vocal at all about worsening city air quality, either. Even after a collection of experts and advocates at Drexel University put together Philly’s first real climate crisis report, no one from Council – including its environmental committee chair – took the needed step of reaching out and finding out more about it.

It’s mind boggling when eyeing the scale of Philly’s air pollution crisis and how it ranks nationally. Philadelphia’s city council is dominated by Black voices, and the city political and advocacy class is dominant with the same. Yet, despite the ghastly burden of air pollution and bad air quality on Black populations, particularly Black children – and particularly as pollution-fueling climate crisis is actually making the Black maternal mortality rates (accounting for 73 percent of pregnancy-related deaths) even worse - there is, eerily, not much noise around the air quality crisis or talk about how to solve it.

Cleaning it Up

One possible way to spark interest and needed action is, again, through the crime conversation already taking place. Since we know, through conclusive research, that air pollution increases crime, policymakers should be leaning on public safety officials to deploy “green living plan”-oriented strategies that focus on the remediation and revival of place. In the past, we’ve called these “place-based strategies.” That includes protecting air because we’re needing to protect the oxygen we breathe in. For example: we now know that one reason violent crime is not as bad now as it was in the 1990s is because of the eventual removal of lead from oil and vehicle emissions. What we’ve seen since then, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, is a nearly 60 percent drop in violent crime overall. We already offered conclusive data showing how increased tree-planting led to a 12 percent drop in violent crime. Without increased tree planting and canopy, and without an immediate way to remove vast sources of carbon-based pollution throughout Philadelphia, we’re missing out on decreased air pollution, decreased chronic disease impacts, and a substantially decreased threat of ongoing violence.

City and state leaders need to also rethink their own quiet and open political relationships with the fossil fuel industry, particularly as it relates to the continued pervasiveness of natural gas in Pennsylvania. It remains inconceivable why city and state leaders would allow policy concessions for the fossil fuel industry that’s worsening air pollution in the region and triggering climate crises – unless, of course, it’s simply about money, political careers and personal interests. But, with natural gas interests spending more than $60 million through lobbying and campaign contributions between 2010-2017, we understand why Pennsylvania is still the only state that hasn’t passed a law taxing natural gas drillers. We then see why it’s so easy for Black-majority small cities in the Philadelphia region like Chester, PA to have a liquefied natural gas plant forced down its throat.

Significant air pollution declines in the region could also be a reality if city, state and Congressional leaders were more transparent about the extent to which combined Biden administration infrastructure and climate crisis-mitigation funds are being committed to Philadelphia. Nationally, between three different federal laws, we know of over $2 trillion in funding for a variety of infrastructure improvement and climate-related projects. We don’t have a complete and organized read on that other than hurried announcements or press releases here and there. Such funds, with public support, could be dedicated to historic air pollution reduction and so-called “decarbonization” projects that could result in Philadelphia being the breathable city it should be for everyone.