Black Student Challenges (The Day After #NationalCollegeDecisionDay)

A time to look more deeply at disproportionate barriers impacting Black college students

A Learn4Life Feature

Learn4Life | @learn4life | #BlackEdChat

#NationalCollegeDecsionDay - as it is affectionately hashtagged - just occurred recently on May 1st. It is typically viewed and treated as a day of celebration and achievement. Students have earned their way into academic next level, the hard work and sweat paying off. But under the confetti, happy selfie pics and household “Congratulations!” banners lies a deeper and more troubling discussion on the challenged state of higher education for Black high school and college students.

What About K-12?

One must first achieve high academic performance and completion of the very crucial K-12 years before considering college. And, yet, there is a tendency for national conversation around education to place a greater focus on the higher education phase that can’t happen … without successful matriculation through K-12. Hence, as the saying goes, current conversation around higher education and the excitement attached to it from pop-culture observances such as #NationalCollegeDecisionDay is like “putting the cart before the horse.”

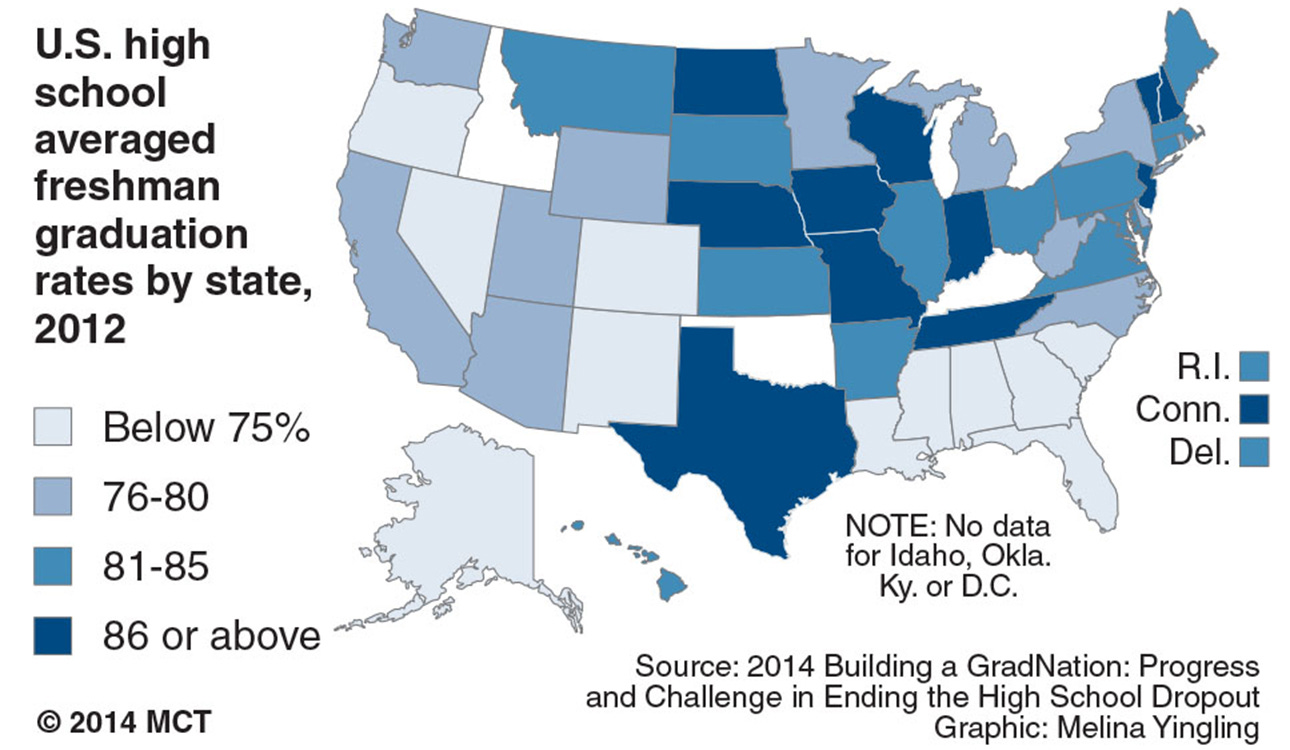

It might be a useful exercise to begin looking more closely at the health of the horse: America’s K-12 schools system, particularly as it relates to the overall health of one of the most distressed demographic groups, African American students. The Kids Count Data Center finds in its data that nearly a quarter of Black high school students nationwide are not graduating on time. That rate has fallen by several percentage points since the 2013-2014 academic year, but it’s still worrisome and much higher than White and Asian non-graduation rates and it’s much higher than the overall national Black population proportion (Native American or Indigenous community numbers are, clearly, in worse shape, as well) …

Black high school graduation rates are also, overall, below the national average, according to National Center for Education Statistics numbers, the most recent aggregated from 2016. It is the second lowest rate, just short above Native American graduation rates …

Overall, at least according to federal data, Black graduation rates are improving. But it’s instructive to look more closely and express worry over those rates in the deep South …

Who’s Enrolling … or Not?

Keeping those graduation rates in mind, it’s now useful to consider who’s enrolling - or who’s able to enroll. Looking at a 2017 National Student Clearinghouse Research Center report, Black students appear the most likely to not be enrolled in college compared to their White, Latino and Asian peers, and they are least likely to complete their degree at the institution where they started. This is particularly pronounced for Black men when broken down by race and gender as shown in the figure below …

Black men (5 percent) and Black women (9 percent) are also below their national population proportion when examining 2016 college enrollment, as explored here. Black male college enrollment has stayed fairly flat since 1976, while Black female enrollment has only grown slightly (Latinx enrollment rates appear to have grown substantially) …

Can they Afford It?

The enthusiasm over college acceptances is that it, perhaps inadvertently, presents a narrative that all is well with America’s K-12 student population. It’s an overwhelmingly “middle-class” narrative that risks ignoring the economic crisis experienced by most Black and Brown K-12 students, especially public school students. A 2015 Southern Education Foundation report discovered that the majority of public school students are living in poverty, more than half (51 percent) during the 2012-2013 school year. Distribution of that poverty is more pronounced in deep Southern states - with massive Black residential populations ….

Black poverty for children under 18 factors prominently …

This is all happening at a time when college tuition is increasing at a rapid pace and into a zone of such financial discomfort that it’s becoming more and more unattainable for families. Census data show household median income unable to keep pace with growing tuition costs …

College tuition continues to explode among private and public four-year institutions …

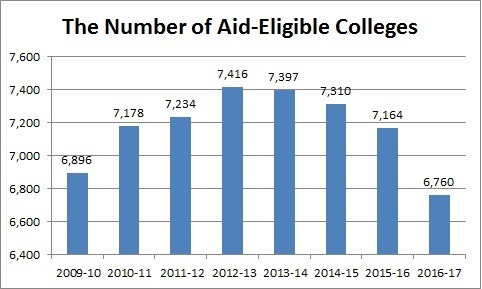

And, so, it’s a relevant question: Can the more economically distressed demographic groups already dealing with bleak economic prospects on the K-12 afford to attend college? It’s a question more relevant and of great alarm to prospective African American college students than most other communities. This is even more problematic considering the sharp decrease in the number of aid eligible institutions

Are They Graduating … From College?

Given the stressful socio-economic conditions faced by Black K-12 students before college, there are concerns over whether they’re adequately prepared to take on the rigors of a higher education. So, are they graduating? An Education Trust report explores that, showing that Black college graduation rates lag behind other racial peer groups

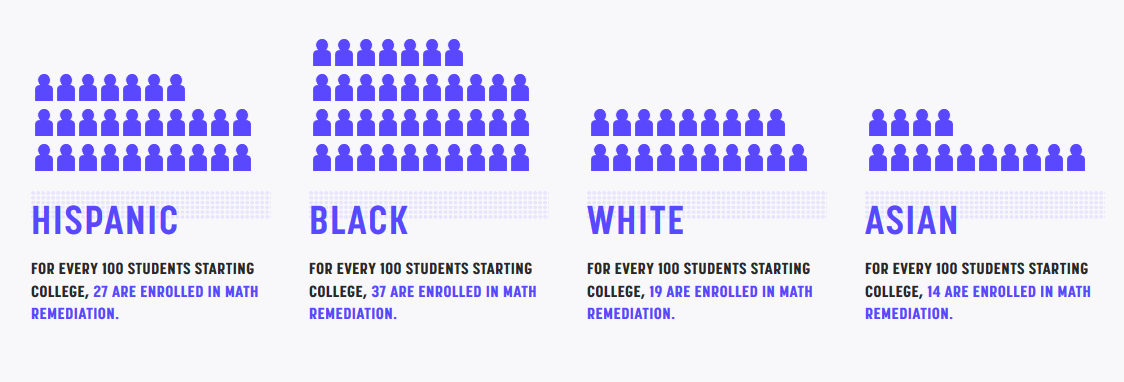

First signs of that problem more also appear in the high percentage of students, nationally, forced into college Math and English remedial course which are not part of the core curriculum once they enter their freshman year. According to the Center for American Progress, 40-60 percent of first year college students require remediation classes in Math and/or English - and on-time, four year completion rates for those students are less than 10 percent. For Black students, it’s worse at 56 percent. Here are other numbers, according to College Complete America

These remedial classes are, tragically, not part of the core curriculum once students enter their freshman year. As a result, it becomes wasted time since the remedial courses are non-credit and don’t contribute to planned majors. It’s also a waste of money and resources that most students don’t have as data above show. And according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, it results in more than $7 billion in accumulated costs for students (who absorb $1.3 billion of that, per Center for American Progress), their families and higher education institutions ... for remedial classes that never count towards credit accumulation. That not only exacerbates negative learning curves, but it further widens academic and quality-of-life gaps for these students that were already existing long before they arrive on campus. The consequences are felt hardest by under-advantaged communities. This presents a serious challenge - and a dilemma - for Black students who are in need of that extra academic edge the most.