Black Migrants Should Ignore the Election Noise

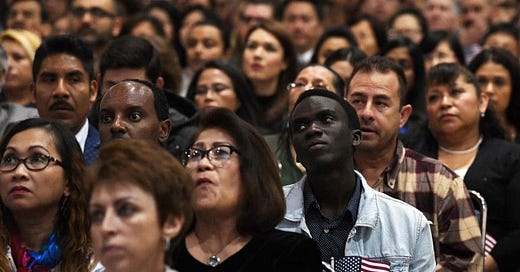

Despite their numbers, African and Caribbean immigrants are largely ignored

Alton Drew feature | Guest Contributor

presented by Reality Check on WURD, airs Monday - Thursday, 4-7pm ET, streamed live at WURDradio.com, in Philly on 96.1 FM / 900 AM | #RealityCheck@ellisonreport

During the first three years of the Trump White House, media in the United States has been especially focused on the administration’s treatment of Central American and Mexican immigrants either trying to enter the U.S. or trying to maintain residence in the country. Little attention is paid to African or Caribbean immigrants by either media or the Democratic Party, a party that has vigorously presented itself as the protector of immigrant rights.

This oversight may be due in part to the minority share of the total immigrant population that Black migrants hold, particularly among so called unauthorized immigrants here in the United States. According to the Migration Policy Institute, approximately 3 percent or 351,000 of the 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States are from the Caribbean. Of this amount, approximately 8,140 unauthorized Caribbean immigrants participate in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a program that allows individuals in the US unlawfully after entering the U.S. as children to receive a two-year period of deferred action from deportation and become eligible for a work permit.

Given that a significant number of Caribbean immigrants are of African descent, race may also be contributing to our “invisible man” status. For the average island man or island girl on the street, keeping our heads low and working our asses off like we have for the last 80 years in this country may be the preferred mode of operation. The reality is that given our small size and the economic benefits derived by the Caribbean region from our working in the United States, a focused and effective political strategy on immigration is necessary.

Remittances: The Life Blood

According to the Migration Policy Institute, remittances from Caribbean immigrants in the United States to the Caribbean region was $12 billion in 2018. The five leading Caribbean countries for remittances are:

Cuba

The Dominican Republic

Jamaica

Haiti

Trinidad and Tobago

These cash out flows are under threat by money laundering laws that strike the fear in correspondent banks, the banks that act as the go-between for a U.S. bank with no branches in the Caribbean and the island nation bank that acts as a depositor for a recipient. With fewer of these banks available, Caribbean immigrants in the United States face increased challenges to getting money back home to their families.

The Political Strategy for Caribbean Immigrants

For the Caribbean immigrant concerned with optimizing income opportunities in the States and maximizing remittances sent back to the Caribbean, influencing economic decisions is key. Our small numbers mean focusing on policy decisions that allow us to earn income, create savings, and transmit excess capital back to the Caribbean.

Racial discrimination is a reality and cannot be severely discounted, but Caribbean immigrants, particularly those who are playing a long-term vision of building up and eventually returning to the region, should not get bogged down in solely race-driven policy initiatives. You will find that some of those initiatives - i.e. the initiative to recognize American Descendants of Slaves (or “#ADOS”) as a distinct group that should receive reparations - contain policy decisions that run counter to the mission of optimizing income and maximizing remittances.

Caribbean immigrants should support candidates who clearly favor relaxing government restrictions that hinder correspondent banking or offer remedies that address the concerns of money laundering while facilitating capital flows between the United States and the Caribbean.

Caribbean immigrants should also throw support behind candidates that are clearly in favor on loosening onerous restrictions on immigration. Outside of tourism, our primary export is a talented, educated, hardworking labor force, one that has been contributing to both the American and Caribbean economies for the last 80 years.