Are Charter Schools Good or Bad for Black Students?

As "school choice" debate ensues, a need to examine charter school effectiveness

a #BlackEdChat feature

Many education experts and seasoned observers of the education reform movement are suggesting charter schools are either facing a pivotal moment or an existential threat. A wave of teacher union strikes, public opinion shifts and moves by policymakers to slow charter growth has prompted renewed concern from K-12 options advocates. University of Massachusetts Jack Schneider proclaimed in a recent Washington Post opinion piece that …

The charter school movement is in trouble. The vanguard of this unrest is organized teachers, political progressives and public education activists. Yet public opinion, even if it is moving more slowly, is tilting in the same direction.

Much of this discussion contains a rather significant racial component as Black and Latino students, disproportionately, constitute a significant share of the national charter school population relative to their overall population share. Between 2000-2016, Black and White student enrollment dropped somewhat (with White student share dropping much more substantially) as Latino enrollment spiked along with a small increase in Asian-Pacific Islander enrollment according to National Center for Education Statistic data …

Glimpses at demographic data also trigger worries from observers that charter schools encourage segregation, particularly in the case of Black children, than discourage it. This conversation becomes more visible with the 65th Anniversary of the famed Brown v. Board of Education decision in the Supreme Court which struck down segregated public education. However, it’s unclear if the debate answers a key question of whether we should be concerned about segregation or achievement. That’s a rather tricky debate considering the academic struggles Black students continue to face overall, particularly in comparison to their peers: on one hand, institutions and governments must do all they can to foster diverse and inclusive educational environments; but, they must also prioritize curriculum quality and student achievement.

In the achievement context, the more important question: Are charter schools are good or bad for Black students? This is an important question as once “minority” students are now representing the majority in K-12 school systems, primarily in traditional public schools and charters.

Even critics admit that the research is still limited on that question given the fact public charters are somewhat relatively new, as researchers Patrick Baude, Marcus Casey, Eric Hanushek, Steven Rivkin conclude in The Evolution of Charter School Quality …

Studies of the charter sector typically compare charters and traditional public schools at a point in time. These comparisons are potentially misleading because many charter-related reforms require time to generate results.

For some clarity, we look at a number of studies and briefings on the topic. In an October 2016 Brookings’ Institution study, researchers Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, Richard V. Reeves and Edward Rodrigue note …

Also important to the segregation discussion is the body of research on the impact of public charter schools. Whereas overall, charter schools across the nation perform only slightly better than regular public schools, the story is different for a subset of charter schools serving overwhelmingly black and poor students in large cities with a so-called “no excuses” education model. Students in these schools have dramatically higher levels of achievement than comparable students attending regular public schools. Studies providing the strongest evidence for the effectiveness of this particular type of charter school take advantage of the requirement that oversubscribed charters use a lottery to determine who among the applicants receives an offer of admission. Comparisons of state test scores, high school graduation rates, and college-going of students who win vs. lose their lottery for admission are, effectively, gold-standard randomized experiments on the impact of these charter schools on student outcomes.

Researchers cited an earlier September 2016 study from colleagues Sarah Cohodes and Susan M. Dynarski …

[O]ne year in a Boston charter middle school increases math test scores by 25 percent of a standard deviation. The annual increases for language arts are about 15 percent of a standard deviation. Test score gains are even larger in high school.

In this case, Black students account for nearly 58 percent of all charter public school students in the Boston public school district, compared to 37 percent of traditional public school students.

Urban Does Better

Susan Dynarski in the New York Times notes in a 2015 article that urban charter schools or charter schools serving specific underserved populations are the better performing charter schools …

Rigorous research suggests that the answer is yes for an important, underserved group: low-income, nonwhite students in urban areas. These children tend to do better if enrolled in charter schools instead of traditional public schools.

This suggests a student-centered or tailored approach is advantageous for the students facing difficult socio-economic circumstances. The critique of traditional public schools is that they are having difficulty adjusting to those needs.

A joint Princeton-Brookings study from 2018 finds similar data three years later …

[M]uch of the same research also finds that a subset of charter schools has significant positive impacts on student outcomes. These are typically urban charter schools serving minority and low-income students that use a no excuses curriculum. When estimates for these highly effective schools aren’t separated from the broader group of charter schools, mostly those in suburbs and rural areas, differences between charter and traditional public schools average out to zero.

Given that the overall distribution of charter school effects is very similar to that of traditional public schools, expanding charter schools without regard to their effectiveness at increasing test scores would do little to narrow achievement gaps in the United States. But expanding successful, urban, high-quality charter schools—or using some of their practices in traditional schools—may be a way to do so. Research findings that show successful charter school expansion, as well as benefits from adopting charter school practices in district schools, lend support to the idea that expanding highly effective charter schools and getting low-performing public schools to adopt their practices may be a way to ameliorate achievement gaps

More data is displayed in an Education Next briefing by Martin West. Nationally, the trend holds up, the same as it did in the Boston study - again, so long as it’s urban charter schools compared to public schools …

We see this holding up in the highly urban and diverse Florida school districts, as studies show …

Focus on the Achievement Gap

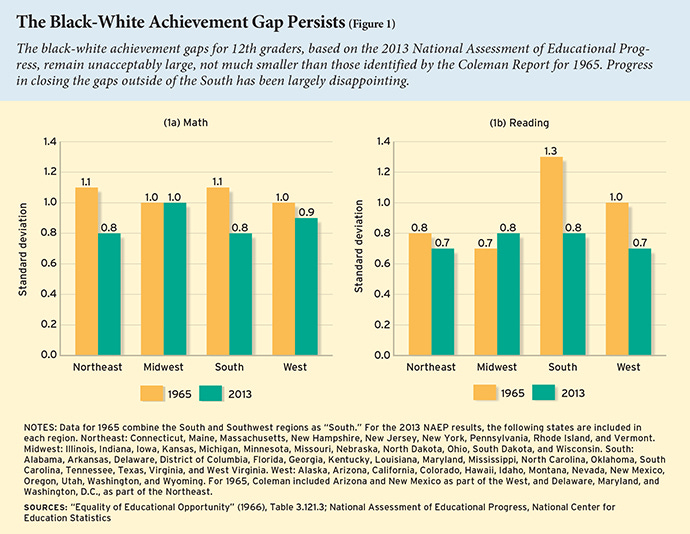

Determining charter school progress is a crucial conversation as policymakers and experts struggle to find the right recipe for Black student achievement. As data below show, those gaps remain unchanged …

But, as enlightening data on the success of urban “no-excuses” model charter schools show, perhaps there is an opening for the broader introduction of a fresh model versus indiscriminate policy action that either limits or altogether eliminates charter programs. Stakeholders on both sides must set aside ideological tensions and, together, parse through the data and craft policy as a result of that exploration. Both should discover that the major differnce appears in the form of a focus on “student-centered” learning and programs that take individual student needs and socio-economic circumstances into account.

sponsor

Change Your Story

Individualized learning programs with a mission to serve opportunity youth. More at Learn4Life.org