an American Academy of Arts & Sciences feature

The story of the United States has always been one of continuing reinvention. That is the story of the American economy as well. The United States was an agricultural nation at its inception, then became an industrial one, then a diversified postindustrial one. At every stage, the nation’s political and economic systems were interconnected, each adjusting to changes in the other. The nation preserved its economic strength through depression and recession, through land wars, cold wars, and trade wars, and through the arrival of the microchip, the megabyte, and the machine-learning revolution.

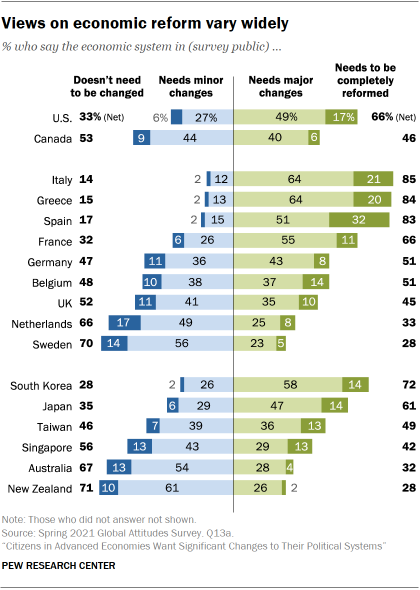

Today, another adjustment is in order. Over the past several decades, the connection between growth and shared prosperity in the United States has not been strong enough. This period has produced a tremendous amount of progress and prosperity. But for many, it has also produced uncertainty, insecurity, and disaffection. Too many families cannot achieve the life they want despite their best efforts, too many communities have not benefited fully from national economic growth, and too many Americans believe the economy does not work for them. In a 2021 survey, 66 percent of American respondents felt that their nation’s economy needs major reforms, and just 6 percent felt it should remain unchanged. There is a widespread sense that more people should be able to partake in the nation’s prosperity.

A major area of concern is the damage that the economy has done to American optimism. In recent polls, just 23 percent of Americans said they believed the nation was heading in the right direction, 55 percent were confident that today’s young people will have a better life than their parents, and 32 percent predicted that the nation’s economy will be stronger in 2050 than it is now. There are many reasons for the prevalence of these views, and it is notable that when Americans are asked about their own personal situation, rather than that of the nation as a whole, their outlook is considerably sunnier. Nonetheless, widespread concerns about economic well-being threaten to tear at the fabric of American life. Those who feel they lack opportunity are prone to distrust political leaders, markets, institutions, and even their own neighbors. A 2019 survey of the United States and other countries found a strong connection between economic pessimism and democratic dissatisfaction. Recent research also suggests that the emotion that best predicts voters’ turn to populist political candidates is not anger but gloom — a sense of malaise and despair that can aggravate long-standing social tensions. When people feel constrained from achieving better lives, they are more likely to distrust the institutions that can help shape a better future for them and for the nation.

Such sentiments are rooted in people’s lived experience. In 2022, poverty rates increased nearly 5 percent and rates of child poverty nearly doubled, as government programs and tax credits enacted during the pandemic expired. Many Americans’ expectations for economic life took hold in the decades following World War II, a time of widespread upward mobility and general - though far from universal - prosperity. Since the 1970s, a significant portion of the country’s traditional industrial base has shut down or moved offshore, leaving some parts of the country behind economically, and reducing the number of paths to better futures for residents. As of 2024, the wealthiest 10 percent of households held over 60 percent of all household wealth. Additionally, the share of the economy that goes to workers in the form of wages has fallen. Homeownership affordability, too, is at its lowest levels since 2007.

Based on cost of living estimates collected by MIT’s Living Wage Calculator, in nearly every American county, a typical wage is not considered livable for a household with one adult and two children. These trends have disproportionally hurt nonwhite Americans and those without a college degree who live outside the major metropolitan areas. The Great Recession that followed the 2008 financial crisis hit these Americans and these communities especially hard.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the economic situation of ordinary working Americans has been improving. Over the last few years—not including the eighteen months after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—the nation has maintained a low unemployment rate. The corresponding tight labor markets have increased wages for low-income workers. One welcome result has been a lessening in inequality: Income growth for the bottom half of the distribution has outpaced growth for the top 10 percent, and gender and racial wealth gaps have also declined. Additionally, notwithstanding the spike in 2022, rates of child poverty fell nearly 44 percent between 1993 and 2019, and then declined further thanks in part to COVID-era government programs. This good news demands close attention. Its causes offer insight into which policies can help create needed economic outcomes.

Metrics such as GDP and the Dow are often used to understand our economy as a whole. Both indicators serve important functions. However, while generally seen as objective, they contain judgments about what is worth measuring and whose welfare is important. Neither of these familiar metrics provides sufficient insight into Americans’ well-being and their relationships to the institutions that structure their lives. Roughly 40 percent of households - and nearly 60 percent of Americans under age thirty - do not own stock, including indirect ownership through retirement plans. Broad measurements like GDP reveal very little about areas or communities that are not keeping pace with the progress seen in other parts of the country. Indicators that do not offer insight into differences along lines of race, gender, or ethnicity risk overlooking long-standing and ongoing disparities. As a result, GDP, the Dow, and similar narrow measurements can obscure as well as reveal. Their prevalence in the nation’s public conversation is a symptom of a prioritization of the well-being of the economy over the well-being of the American people.

A twist on a famed social psychology experiment offers evidence of how broken trust can worsen economic decision-making. Children were administered the marshmallow test, a test of grit and patience, in which they are offered a marshmallow with the choice of eating it immediately or waiting for an experimenter to deliver an extra marshmallow. In this iteration, children were first primed to trust or distrust the experimenter. Before the marshmallow test, the children were given art supplies. The experimenter then told the children they could use these supplies or could wait until the experimenter returned with even better materials. For half of the children, the experimenter did in fact return with the premium crayons and stickers. For the other half, though, the experimenter returned and apologetically explained that there were no better supplies after all. The experimenter then administered the marshmallow test. Those children who received the promised supplies were significantly more likely to wait than those who did not. This reaction seems reasonable. Children who had been conditioned not to trust the experimenter had little reason to believe that waiting would yield an additional marshmallow, whereas those who found the system to be fair were happy to delay gratification for the future reward they were sure would come. When promises are broken, when institutions act unfairly, it is easy to lose trust. If people feel that the economy is not delivering for them, is it any wonder that they lose faith it ever will?

In the decades immediately following World War II, the country generally grew together economically, with gains distributed relatively evenly across the income distribution, albeit unequally along lines of race and gender. Then, beginning around 1980, the top income earners began pulling away from everyone else, which produced increasing disparities in wealth and income. Over the last ten years or so, wealth and income inequality leveled off and began to fall. But the inequality that exists today has, for some Americans, epitomized the unfairness of the political and economic system. Many members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Commission on Reimagining Our Economy share this view and are particularly concerned about the ways the rich use their fortunes to exert political power and to preserve their advantages in the marketplace. Other members of the Commission are less concerned about inequality, per se. In their view, what matters most is to secure the well-being of those at the bottom of the income distribution and to ensure overall, continuous economic growth that benefits everyone; whether the rich become richer at the same time is unimportant.

Reflecting these varied views, the Commission’s recommendations seek to do more than simply manage economic outcomes. Some of their proposals seek to remedy unfair market-generated disparities after the fact through taxes and government benefits, a process often called “redistribution.” In addition, the Commission advocates for what is known as “predistribution”: structuring the economy in the hope that some of its most severe disruptions and unfairness might not occur in the first place, and would therefore not have to be remedied later. Predistributionary policies aim to spread economic opportunity and to create a more open, competitive economic playing field for individuals, firms, and industries.

Whether focused on redistribution or predistribution, the Commission’s recommendations ask for action from a variety of institutions. Some reforms can be accomplished through the private sector or civil society, especially community organizations. As has been the case at other times in the nation’s history, governments must also be involved in improving economic opportunities and outcomes for a wide swath of Americans. In some cases, government can help address market deficiencies by paying special attention to those who would otherwise fall through the cracks. In other cases, government itself is the cause of the problem. Federal, state, and local governments have adopted policies that are anticompetitive, disproportionately benefit the wealthy, deepen racial disparities, and generally contribute to the sense that the economy is rigged. Some of these policies were well-intentioned but are now outdated or have become counterproductive. No matter their origin, when policies create a barrier to security or opportunity, or when they fail those who need assistance, they should be reexamined and revised. Doing so will not only improve economic outcomes but will also help restore Americans’ faith in the nation’s institutions.

The Commission is guided by the idea that economic well-being fundamentally shapes the well-being of democracy, just as democratic well-being shapes the well-being of the economy. This is what scholars call “political economy.” The concept of a political economy is rooted in the idea that markets do not automatically or naturally exist. They are created by people and operate according to rules, which are usually set by governments. As in sports, what one notices about markets are the achievements of the players, not the deliberations among the referees and rulemakers. Who would want to watch the National Basketball Association debate the dimensions of the court or the duration of the shot clock? But rules and their enforcement shape how, and how fairly, the game is played. Analysis of political economy includes not only supply and demand curves but also consideration of voice and representation. Political economy is not a new concept in the United States. It was articulated by the nation’s founders from the outset. As James Madison put it in 1787, “A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations. . . . The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation.”

Recommendations to bolster economic opportunity and security, then, are aimed at identifying changes in the design and the administration of the institutions that are necessary to make those concepts a lived reality for most people. Solutions are meant to foster Americans’ recognition that their future is intertwined with the fates of their neighbors, their community, and their country. Reducing unfairness in markets and in government policies can improve these types of civic connections. A political economy of fairness can foster a culture of fairness.

* * *

In December, the Council of State Governments (CSG) will convene its annual meeting of state legislators in New Orleans from around the country to discuss some of the most pressing public policy issue their constituents are faced with today. One of those discussions will be on December 5th and is entitled “Enhancing Economic Mobility and Equity: Advancing a People-First Economy.” Experts will unpack Advancing a People-First Economy, the final report of the Commission, a project of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AMACAD). It will be moderated by theB|Enote Publisher Charles Ellison.